Looking at Luke 16:19-31, Jason Smith once again wove in art as an example to look at the gospel from a new angle.

Jason began this sermon with an invitation to consider negative space, telling a story of a Dutch artist visiting the Moorish palace of Alhambra in Spain. “He had visited this beautiful Moorish site before as a young art student, but this time would forever change how he saw things.”

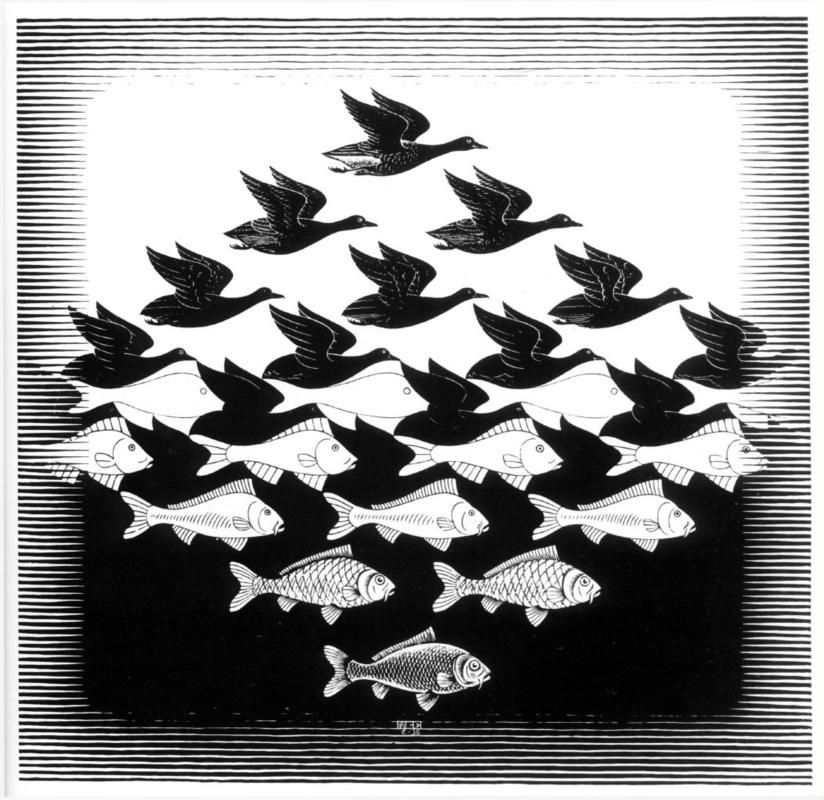

The geometric abstractions that patterned the walls — closely fitted, repeated patterns that overlap without gaps — are called tessellations. The pattern starts with a focal point — the subject of the image. The subject is defined by the barriers at its edges. The part of the image beyond the barrier of the subject (and not a focal point) is in the negative space. But in the repetition of a pattern the subject and the secondary figure switch places. As is the nature of a pattern (sometimes referred to as “Repetition Art”) this sequence repeats itself over and over.

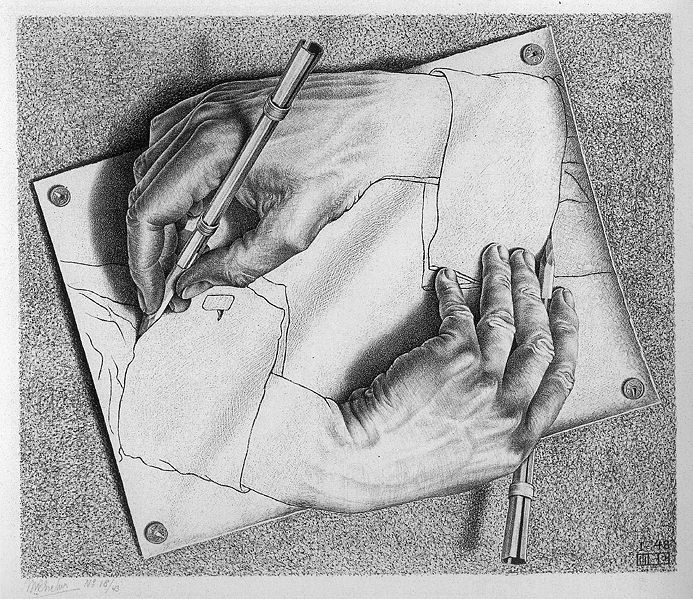

When the Dutch artist walked past the gate, he observed the surrounding structures and patterns that the North African Moors brought to Spain. Later in response he would illustrate the structures and patterns of a world he imagined. This time he brought a sketchpad with him and copied the tessellated patterns that he found on the walls. He would repeat the lessons that he learned beyond the gates of Alhambra in his later drawings, woodcuts and other printworks. He became known to the world as M.C. Escher, the creator of elaborate patterns and imaginative structures that resemble a stretched and contorted Alhambra that has been warped upside down and inside out.

In the Gospel reading of Luke 16:19-31 we hear of a similar story. Near the early 30’s of the first century a thirty-something year old rabbi from Nazareth set his eyes toward the gates of Jerusalem. He had preached his way through this Mediterranean, Roman coastal possession from the Galilean Sea. And now he travelled to the capital city of Jerusalem, in Judea. And as he journeyed toward the gates of Jerusalem, he observed the structures and patterns of the world around him. In response he illustrated the structures and patterns of the world to come. He became known to the world as Jesus Christ, the creator of elaborate parables and imaginative homiletic structures that stretched and contorted the City of Man, warping it upside down and inside out into the City of God. Christ saw that, like Alhambra, the walls that held up the societal structures of Jerusalem were built by the religious rulers. Covering the pillars of the Law, the Pharisees overlaid patterns of greed and self-serving bias. In response Jesus drew to himself a people of God and self-sacrifice. Jesus and M.C. Escher both employed the art of illustration. It is important here that we recognize that a parable is a sermon illustration. Jesus used sermon illustrations to redraw how we imagine the world that we see around us. Just like M.C. Escher’s tessellations, Jesus’ parable in Luke 16 follows the principles of patternmaking. The way that they work starts with a main figure and focal point that we can call the subject of the imagery. The subject is defined by the barriers surrounding him. The secondary figure beyond the barrier of the subject (and not a focal point) is in the negative space. But in the repetition of the pattern the subject and the secondary figure switch places. Theologically this pattern is sometimes referred to as “the Great Reversal.” And as we will see, it repeats itself over and over in Scripture.

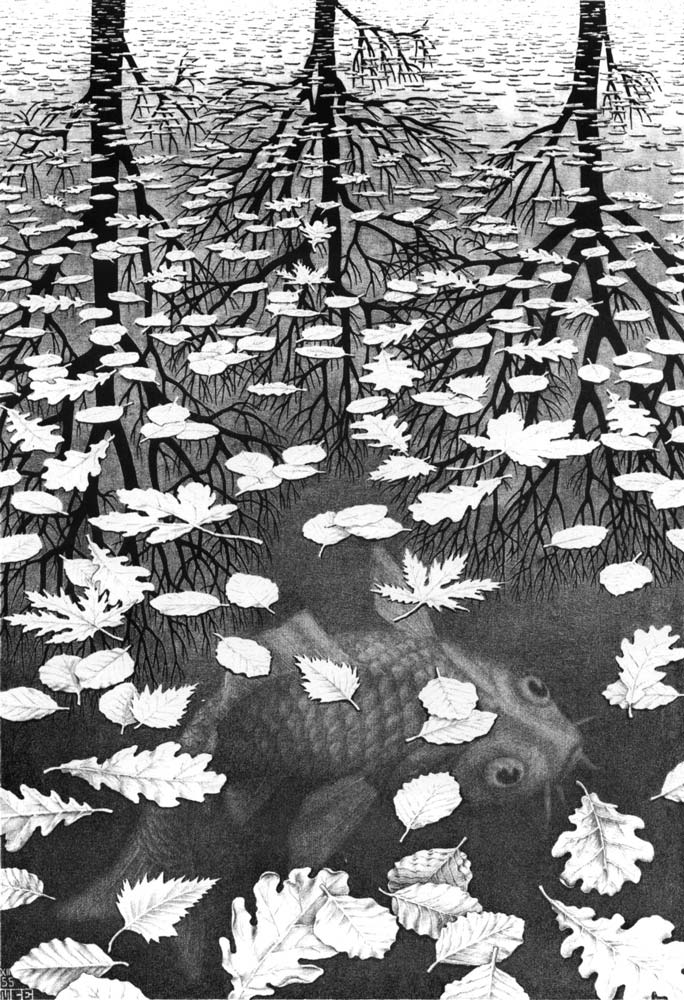

Jason continues to weave together subject and background, the barriers surrounding them, and the reversal of roles in the gospel story. Hear more in the audio below. Also below are several Escher images referenced in Jason’s sermon.